BRISMES Statement on Settler Colonialism, Decolonisation and Antisemitism

In recent years, there have been growing movements on university campuses calling for the decolonisation of higher education institutions, through which students would be exposed to a wider range of perspectives, particularly those from and rooted in the lived experiences of people in the Global South. In many cases, universities have declared their support for such calls, incorporating “decolonising the curriculum” into university structures, learning experiences, and anti-racist vision documents and action plans.

Despite this ostensible commitment to the decolonisation of higher education, in the wake of Hamas’s October 7th violent assault and Israel’s horrific war on Gaza, BRISMES has been witnessing a worrying trend of attacks on decolonial and anticolonial scholarship and perspectives in relation to analyses of the situation in Israel-Palestine. In particular, accusations have increasingly conflated the use of ‘settler colonialism’ – as a descriptor of the policies of dispossession and displacement implemented by the Israeli state against Palestinians – with support of terrorism and/or antisemitism (for example, see here, here, and here). This has worsened an already challenging environment for speaking about Palestinian human rights on university campuses. In particular, academic freedom and freedom of speech on Israel-Palestine have been subject to significant and unfounded restrictions due to universities’ widespread adoption of the IHRA definition of antisemitism, as demonstrated in a recent report by BRISMES and the European Legal Support Centre.

BRISMES is deeply concerned that these attacks on settler colonial, anti-colonial, and decolonial frameworks could lead to a rolling back of the progress that has been made in introducing evidence-based historical analyses emanating originally from Global South scholars, and believes that efforts to stigmatise the findings of these scholars constitute a serious threat to academic freedom and freedom of speech. Building on our extensive collective expertise as scholars of the Middle East, we seek to clarify that the settler-colonial framework, including concrete calls for the decolonisation of Palestine, are neither antisemitic, nor supportive of terrorism. In order to demonstrate that such work is in fact a well-established and respected scholarly field, an appendix accompanying this document describes in detail the arguments made by scholars who argue that Israel-Palestine should be understood as a context of settler colonialism.

Settler colonial studies form part of an established and well-respected body of knowledge in several disciplines and provide analytical tools for understanding the historical development and/or contemporary policies of numerous countries, including the United States, Canada, Australia, Argentina, and South Africa, yet has been portrayed as illegitimate when applied to the context of Israel-Palestine. Critics of settler colonialism in relation to Israel-Palestine claim that the absence of a colonial metropole means that Israel cannot be a settler colony, and that the presence of indigenous Jewish communities in historic Palestine prior to the establishment of the State of Israel mean that Jewish Israelis cannot be settlers, both of which are misunderstandings or mischaracterisations of the claims of settler colonial scholarship.

In particular, in efforts to invalidate scholarship on settler colonialism, its opponents present the calls for decolonisation and anticolonialism outside of their historical context and cast them as calls to displace and/or eliminate all Jews living in Israel. This is in spite of the total absence of these racist elements in settler colonial scholarship, which is driven by a horizon of liberation, antiracism, and justice. If this misleading interpretation were to prevail, then by analogy the decades-long demand to dismantle apartheid in South Africa would have been construed as a demand to destroy South Africa and/or kill or displace all white South Africans. In contrast, a historically-informed understanding of decolonisation advocates for Palestinian rights and self-determination, and argues that this should be carried out not through processes of elimination of the settlers but through a process that revokes the privileges of the settler polity and creates a form of governance based on equality and freedom for all inhabitants.

The efforts to cast settler colonial claims as antisemitic have emerged at a time when antisemitism, Islamophobia, and anti-Palestinian racism are on the rise across the UK, Europe, North America, and elsewhere. Manifestations of hate towards Jews, Muslims, Arabs and Palestinians must be challenged wherever they appear, not least in higher education institutions. However, the labelling of certain ideas and concepts, including but not limited to, settler colonialism, decolonisation, and anti-colonialism, as antisemitic or support for terrorism, constitutes a very dangerous narrowing of the parameters of what constitutes politically-acceptable speech, and repeatedly morphs into Islamophobia. 1

BRISMES strongly warns against the assumption that scholars of the MENA region or students and activists who voice their opposition to the Israeli regime in terms of settler-colonialism, decolonisation and anticolonialism are motivated by antisemitism rather than an understanding of historical developments in the region. We see the attacks on settler colonial studies, and on decolonial and anticolonial perspectives, as part of the wider attacks on critical scholarship that we have witnessed in recent years, in particular regarding critical race theory and trans-inclusive scholarship.

In all cases, it is imperative to uphold the rights of staff and students to use concepts and theoretical frameworks rooted in the historical and lived experiences of colonised peoples and to allow the voices of those living under colonialism to be heard. Universities have a legal obligation to uphold freedom of expression for staff and students, which is paramount for academic freedom and the pursuit of knowledge.

1 In a recent report, the Rutgers Center for Security, Race and Rights, following an analysis of US public debate on Israel-Palestine, finds that, “when Muslims and Arabs in America defend the rights of Palestinians or criticize Israeli state policy, they are often baselessly presumed to be motivated by a hatred for Jews rather than support for human rights, freedom, and consistent enforcement of international law”, arguing that such presumptions are informed by Islamophobia.Rutgers Center for Security, Race and Rights, ‘Presumptively antisemitic: Islamophobic tropes in the Israel-Palestine discourse’, November 2023

Appendix: Academic Arguments for Settler-Colonialism in Israel-Palestine

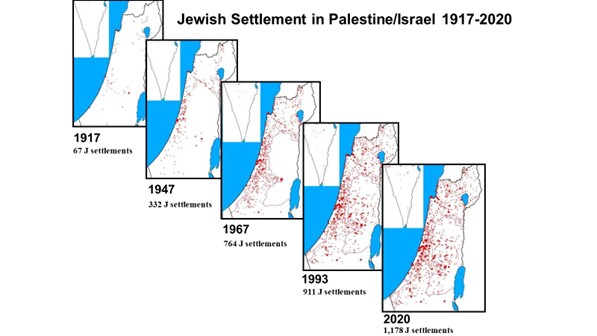

These maps depict the growing number and geographic expansion of Jewish settlements in the area that had been Mandatory Palestine, from 67 settlements in 1917 to 1,178 settlements in 2020. It does not show Palestinian villages, of which about 500 were destroyed in the aftermath of the 1948 war.

©Oren Yiftachel

A well-established field of scholarship has shown how colonialism operates as a mode of domination, via the extraction of material resources, exploitation and dispossession, enforced by violence and justified by racist ideologies. Settler colonialism is structured more directly by territorial conquest via mass settlement: whereby a settler population seeks to replace native peoples, ecologies and modes of relations through a combination of killing, ethnic cleansing, land dispossession, partition, transfer and cultural assimilation (see amongst others, Estes 2019, Karuka 2019, Kauanui 2008 and Wolfe 2006). In order to help educate scholars and the wider public on the framework of settler colonialism as it applies to Israel-Palestine, BRISMES has created this appendix, which lays out some of the main arguments that scholars make as to why and how Israel-Palestine should be understood as a settler colonial context.

Before Israel’s establishment in 1948, the Zionist movement described itself as a settler colonial enterprise. Theodor Herzl promised European leaders that the ‘State of the Jews’ would “form a portion of a rampart of Europe against Asia, an outpost of civilization as opposed to barbarism” (Herzl 1997). Vladimir Jabotinsky described Jewish colonists in Palestine as “alien settlers” intent on thwarting the indigenous population’s aspiration to rule themselves and their country (Jabotinsky 1923). Palestinian, Israeli and international scholars have since shown how the Zionist movement, with the support of imperial Great Britain and, later, the Israeli state, has sought to maximise the land it controls while minimising the number of Indigenous Palestinians under its sovereign authority (Abu-Lughod and Abu-Laban, 1974; Khalidi 2021; Pappe 2008; Rodinson 1973; Said 1979; Sayegh 1965; Sayigh 1979; Veracini 2013; Wolfe 2006; Zreik 2023; Zureik 1979). Settler-colonial and decolonial analyses have highlighted how the space of Mandatory Palestine has been both conceptually and physically de-Palestinianised and ‘Judaised’ (Falah, 1991; Dana and Jarbawi, 2017; Blatman 2017).

Scholars of Israel-Palestine who draw on settler colonialism as a framework have demonstrated how racial dimensions of Israeli power structures manifest themselves in basic laws, citizenship categories and modes of governance (e.g. Lentin, 2018; Rouhana and Sabbagh-Khoury, 2015; Tatour, 2019), as well as the processes through which Palestinians have been dispossessed (Amara 2013; Cohen and Gordon 2018) and the ideological formations and discourses used to justify and normalise Palestinian displacement (Perugini 2019; Shalhoub-Kevorkian 2015). Scholars have shown how Zionist settlers who immigrated first to Palestine and, after 1948, to Israel, displaced and then replaced the majority of the indigenous Palestinian population. Indeed, approximately 750,000 Arab Palestinians either fled or were expelled during the war of 1947-48 and despite UN Resolution 194 underscoring their right to return to their homes, Israel prevented them from doing so.

After 1948, the newly-created Israeli state enacted the massive confiscation of Palestinian lands (Sa’di 2013; Khamaisi 2003). By 1951, the Israeli state effectively owned 92 percent of the land within its territory, up from 13.5 percent in 1948 (Forman and Kedar 2004). Of the 370 new Jewish settlements established soon after 1948, 350 were built on or in proximity to Palestinian villages that had been destroyed (Kedar and Yiftachel 2006). Also by 1951, the 750,000 Palestinians who had become refugees in 1948 were “replaced” by a similar number of Jewish immigrants, both Holocaust survivors from Europe and Mizrahi Jews from Arab-majority countries, thus transforming the nascent state’s ethnic composition without altering its overall population size (Cohen 2002). These and other studies have argued that settler colonial elimination and replacement have constituted the foundational logics of the constitution of the State of Israel, which persist into the present (Jabary Salamanca et al. 2012).

In line with Patrick Wolfe’s (1998) argument that settler colonialism is not an event but a structure, scholars of settler colonialism have argued that the separation of the Palestinian people from their land was embedded in Israel’s laws, policies, and practices after 1948 and swiftly became part of the overarching logic of the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem, Gaza Strip and the West Bank following the 1967 war (Said 1980; see also B’Tselem 2002). They have furthermore argued that these same logics are structuring Israel’s 2023-2024 war on the Gaza Strip, which is characterised not only by the immense numbers of civilians killed but also the forced displacement of over 2 million Palestinians, and the destruction of civilian infrastructure, including hospitals, schools, residential homes and agricultural land. This level of violence has the explicit aim of making Gaza uninhabitable, further disconnecting its population–largely constituted of 1948 refugees–from their land, ecology and space of life. Indeed, it could be argued that the events of the recent months represent some of the most intense moments of settler colonialism and its attempt to eliminate the indigenous Palestinian population in the history of Israel-Palestine.

Indicative Bibliography of Scholarship on Israel-Palestine and Settler-Colonialism

Abu-Lughod, Ibrahim and Baha Abu-Laban (eds) (1974) Settler Regimes in Africa and the Arab World: The Illusion of Endurance. Wilmette, IL: Medina University Press International.

Amara, Ahmad (2013) "The Negev land question: Between denial and recognition." Journal of Palestine Studies 42(4): 27-47.

Blatman, Naama (2017) "Commuting for rights: Circular mobilities and regional identities of Palestinians in a Jewish-Israeli town." Geoforum 78: 22-32.

Cohen, Yinon (2002) "From Haven to Heaven: Changes in Immigration Patterns to Israel," in Levy D. and Y. Weiss (eds), Challenging Ethnic Citizenship: German and Israeli Perspectives on Immigration. New York: Berghahn Books: 36-56.

Cohen, Yinon and Neve Gordon (2018) "Israel’s biospatial politics: Territory, demography, and effective control." Public Culture 30(2): 199-220.

Dana, Tariq and Ali Jarbawi (2017) ‘A Century of Settler Colonialism in Palestine: Zionism’s Entangled Project.’ The Brown Journal of World Affairs 24(1): 197-220.

Estes, Nick (2019) Our History is the Future: Standing Rock versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. London: Verso Books.

Evri, Yuval, and Hagar Kotef (2022) ‘When Does a Native Become a Settler? (With Apologies to Zreik and Mamdani)’. Constellations 29(1): 3–18.

Falah, Ghazi (1991) ‘Israeli “Judaization” Policy in Galilee.’ Journal of Palestine Studies 20(4): 69-85.

Forman, Geremy, and Alexandre (Sandy) Kedar (2004) ‘From Arab Land to “Israel Lands”: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinians Displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948.’ Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 22(6): 809–30.

Herzl, Theodor. (1997) The Jews' state: A critical English translation. Jason Aronson, Incorporated.

Jabary Salamanca, Omar and Mezna Qato, Kareem Rabie, Sobhi Samour (2012) “Past is Present: Settler Colonialism in Palestine,” Settler Colonial Studies 2(1): 1-8

Jabotisnky, Vladimir Ze'ev. (1923) " The Iron Wall."

Karuka, Manu (2019) Empire’s Tracks: Indigenous Nations, Chinese Workers and the Transcontinental Railroad. Oakland: University of California.

Kauanui, J. Kehaulani (2008) Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity. Durham: Duke University Press.

Kedar, Alexandre and Oren Yiftachel (2006) ‘Land Regime and Social Relations in Israel,’ in de Soto H. and Cheneval F. (eds), Swiss Human Rights Book, Vol. 1, Zurich: Ruffer and Rub, 2006, 129-146.

Khalidi, Rashid (2021) The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017. New York: Picador.

Khamaisi, Rassem (2003) “Mechanism of land control and territorial Judaization of Israel,” in Al-Haj, Majed and Uri Ben-Eliezer (eds) In the Name of Security. Haifa: Haifa University Press: 421-449.

Lentin, Ronit (2018) Traces of Racial Exception: Racializing Israeli Settler Colonialism. London; New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Murphy, Shannonbrooke (2012) ‘The Right to Resist Reconsidered,’ in Keane, David and Yvonne McDermott (eds) The Challenge of Human Rights: Past, Present and Future. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Pappé, Ilan (2008) ‘Zionism as Colonialism: A Comparative View of Diluted Colonialism in Asia and Africa.’ South Atlantic Quarterly 107(4): 611–33.

Perugini, Nicola (2019) ‘Settler colonial inversions: Israel's ‘disengagement’ and the Gush Katif ‘Museum of Expulsion’ in Jerusalem,’ Settler Colonial Studies, 9(1): 41-58

Rodinson, Maxime (1973) Israel - A Colonial-Settler State, Anchor Foundation.

Rouhana, Nadim N., and Areej Sabbagh-Khoury (2015) ‘Settler-colonial citizenship: Conceptualizing the relationship between Israel and its Palestinian citizens.’ Settler Colonial Studies 5(3): 205-225.

Sa'di, Ahmad H (2013) Thorough Surveillance: The Genesis of Israeli Policies of Population Management, Surveillance and Political Control Towards the Palestinian Minority. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Said, Edward (1979) ‘Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Victims’. Social Text 1: 7–58.

Sayegh, Fayez (1965) Zionist Colonialism in Palestine. Beirut: Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

Sayigh, Rosemary (1979) Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries: A People’s History. London: Zed Books.

Shalhoub-Kevorkian, Nadera (2015) Security Theology, Surveillance and the Politics of Fear. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tatour, Lana (2019) ‘Citizenship as Domination: Settler Colonialism and the Making of Palestinian Citizenship in Israel.’ The Arab Studies Journal 27(2): 8–39.

Veracini, Lorenzo (2013) ‘The Other Shift: Settler Colonialism, Israel, and the Occupation.’ Journal of Palestine Studies 42(2): 26–42.

Wolfe, Patrick (1999) Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event. London: Cassell.

Wolfe, Patrick (2006) ‘Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.’ Journal of Genocide Research 8(4): 387–409.

Zreik, Raef (2016) ‘When Does a Settler Become a Native?’ Constellations 23(3): 351–64.

Zreik, Raef (2023) "What’s the Problem with the Jewish State?" in Sa’di, Ahmad H and Nur Masalha (eds) Decolonizing the Study of Palestine: Indigenous Perspectives and Settler Colonialism after Elia Zureik: 73.

Zureik, Elia T (1979) The Palestinians in Israel: A Study in Internal Colonialism. London: Routledge.